the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Film and the Arts

August '17 Digital Week I

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 02 August 2017 02:02

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Going in Style

Blood Alley

Amnesia

Barbet Schroeder’s latest, Amnesia—a slow-boiling drama about an German woman whose isolated existence is disturbed by a young man whose appearance leads to terrible revelations—is anchored by Marthe Keller’s lovely, understated performance in the lead.

Based on the 2011 treacly smash-hit French comedy The Intouchables, the Argentine version, Inseparables, is even more sentimental and crude in its story of a wealthy paraplegic and the working-class assistant who brings excitement into his life. The lone Amnesia extra is Your Mother and I, a fine short by British-Canadian director Anna Maguire.

July '17 Digital Week III

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 26 July 2017 02:37

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Barber of Seville

(Deutsche Grammophon)

(PBS)

(Warner Bros)

The final season of the popular series about the quintet of “liars”—Aria, Emily, Hanna, Spencer and Mona—comprises a breakneck progression of 20 episodes culminating with one of the most bizarre TV twists since “Who Shot J.R.”: a twin of one of the gals appears as the infamous D.A., improbably controlling what’s going on.

Yet despite such silliness, the wrap-up is dramatically satisfying. Bonus features comprise several featurettes, wrap party “episode” and deleted scenes.

Film review—“The Midwife” with Catherine Deneuve and Catherine Frot

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Monday, 24 July 2017 02:47

- Written by Kevin Filipski

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Catherine Frot in The Midwife (Music Box Films) |

July '17 Digital Week II

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 19 July 2017 01:54

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Kong: Skull Island

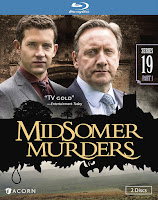

(Acorn)

The Artist’s Garden—American Impressionism

Ron Naveen has been counting penguins for decades. If that seems funny, it’s not: he and his colleagues’ numbers are important indicators of how climate change affects various species in Antarctica, and this informative documentary lays out the continued importance of their ongoing scientific studies.

Directors Peter Getzels and Harriet Gordon also provide beautiful images of the Antarctic habitat, which might convince even the most hardened climate-change denier about what we’re in danger of losing. Extras include additional scenes.

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up