the traveler's resource guide to festivals & films

a FestivalTravelNetwork.com site

part of Insider Media llc.

Film and the Arts

Broadway Review—“The Parisian Woman” with Uma Thurman

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 05 December 2017 03:02

- Written by Kevin Filipski

The Parisian Woman

Written by Beau Willimon; directed by Pam Mackinnon

Performances through March 11, 2018

|

Uma Thurman and Marton Csokas in The Parisian Woman (photo: Matthew Murphy) |

The Trump era will undoubtedly beget other plays about what his election wrought, but Beau Willimon’s The Parisian Woman, an updated rewriting of Henry Becque’s 1885 French comedy La Parisienne, and concerning the high-society wife of a well-connected Washington lawyer who wants a hoped-for judgeship from the new president, gets a head start.

There are disparaging references to Trump’s predilection for Twitter and his listening to the last person he saw in this tidy but static one-act drama that’s a slight disappointment from a writer whose political bona fides were brought to bear with the play Farragut North (which became the George Clooney film The Ides of March) and the Netflix series House of Cards. Willimon writes literate dialogue with acid dripping from it, but his cardboard characters’ machinations do little more than provide for the audience’s amusement and also, finally, bemusement.

It’s obviously how Washington operates—we witness the nastiness behind the scenes—but The Parisian Woman doesn’t so much illuminate as show it, so we see the results without much insight. Chloe, liberal wife of conservative tax lawyer Tom, is first seen with middle-aged banker Peter, with whom she’s having an affair (the spouses apparently have a no-talk policy about extracurricular activities). Peter’s undying love gives her the upper hand when she needs a favor: for Peter to whisper in the president’s ear about her husband’s availability for the court vacancy.

Also used by Chloe is Jeanette, Trump’s pick to lead the Federal Reserve (and seemingly modeled after Janet Yellen, the current Fed chairman), a D.C. veteran who becomes a close confidant of Chloe’s, at least until she realizes that her own daughter Rebecca—a recent Harvard law grad with a bright political future ahead of her—has become a willing pawn in Chloe’s game.

Much of the play consists of conversations in three locations—Chloe and Tom’s living room; the balcony of Jeanette’s home; and a ritzy restaurant (the stylish sets are by Derek McLane)—and director Pam Mackinnon has trouble sustaining the forward motion of a play that sits around for much of its length. That it’s only 90 minutes helps, and the final scene climaxes with another Trump allusion that’s a well-timed punch line.

Josh Lucas (Tom), Marton Csokas (Peter), Philippa Soo (Rebecca) and Blair Brown (Jeanette) give persuasive support, although Brown often barks too much like a bitchy Elaine Stritch. Making a smashing Broadway debut is Uma Thurman, whose Chloe is self-confident, shrewd, smart-looking and impossibly elegant (Jane Greenwood did the dead-on costumes): even how she lounges while sipping Sancerre is charming. Thurman makes The Parisian Woman look better than it really is.

The Parisian Woman

Hudson Theatre, 141 West 44th Street, New York, NY

ParisianWomanBroadway.com

Classical Music Review—Barbara Hannigan at Park Avenue Armory, on CD/DVD/Blu-ray

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Sunday, 03 December 2017 17:41

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Barbara Hannigan

November 18, 2017

|

Barbara Hannigan performing Satie at Park Avenue Armory |

Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan is no stranger to daring programs, which she proves again with her recent stunning Erik Satie recital at the Park Avenue Armory, a new CD of music by George Gershwin, Alban Berg and Luciano Berio, and a concert Blu-ray of her singing more Berg and another of her contemporary favorites, Gyorgy Ligeti.

At the Armory, Hannigan paired with estimable pianist Reinbert de Leeuw for two programs. I missed the first, of songs by the Second Viennese School, but the second, of works by Satie—the minimalist French master best-known for his elegant miniatures Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes—was revelatory not only in performance but in the presentation.

As the audience waited outside the Armory’s intimate Board of Officers Room, the doors opened, de Leeuw began playing Satie’s ballet Uspud, and Hannigan walked barefoot through the crowd holding a candle. After she entered the room, the audience followed, taking seats arrayed around the piano. (The semi-darkness hampered some from taking their seats promptly and properly: one unfortunate soul tripped and fell.) As de Leeuw finished his crisp reading of the half-hour work, Hannigan walked up to a second-level balcony overlooking the room where she began singing Satie’s masterly Socrate—originally written for four female voices—and she simply mesmerized everyone in the room, acting out the quartet of characters, including Socrates, in this astonishing 40-minute work.

Hannigan’s dramatic intensity was evident throughout the performance; she stalked, walked, climbed all over the stage, even turning the pianist’s music pages, and it was impossible to look away from her, whatever she was doing. Too bad some of her most memorable moments while on the balcony were missed by audience members seated with their back to her.

If you’ve never seen Hannigan live, a Blu-ray release of her 2015 performance with the London Symphony Orchestra is available on the LSO Live label. Hannigan’s typical focus—encompassing richly detailed singing and magnetic stage presence—as she performs Berg’s Fragments from “Wozzeck” and Ligeti’s spectacularly nonsensical Mysteries of the Macabre (the latter she sings in a ridiculously silly/sexy get-up) shows off the soprano at her bewitching best, complemented by the LSO and conductor Simon Rattle, who also play Anton Webern and Igor Stravinsky.

|

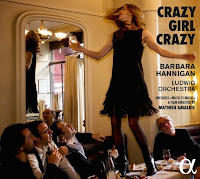

Hannigan's Crazy Girl Crazy CD |

Hannigan herself is conductor on her latest CD, Crazy Girl Crazy, on the Alpha Classics label, in which she collaborates with the Ludwig Orchestra on a new arrangement of Gershwin’s Girl Crazy suite, Berg’s suite from his opera Lulu (I’d love to have the chance to see Hannigan take on that challenging role), and Berio’s wordless pyrotechnic exercise, Sequenza III. Hannigan of course easily traverses this wide-ranging program, her impassioned takes on Gershwin and Berg as impressive as her coughing, whispering, shrieking Berio gymnastics. A great bonus is a DVD of French actor Mathieu Amalric’s short film about Hannigan at work, Music is Music, which provides a further visual component to Hannigan’s dazzling artistry.

Barbara Hannigan

Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY

armoryonpark.org

November '17 Digital Week IV

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Wednesday, 29 November 2017 23:11

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Blu-rays of the Week

Animal Factory

(Arrow)

Actor Steve Buscemi directed this gritty 2000 drama based on the exploits of convict Eddie Bunker (called Ron Decker in the film, and played by an intense Edward Furlong), who gets a 10-year sentence at San Quentin and finds himself under the watchful eye of veteran prisoner Earl Copen (a fine Willem Dafoe).

Even if his film breaks no new ground in the prison genre, Buscemi has made a credible, even sympathetic look at what men behind bars will do to survive. The Blu-ray transfer is quite good; extras include a commentary and featurette on Bunker.

Battle Cry

Hell on Frisco Bay

(Warner Archive)

In 1955’s Battle Cry, young men are seen moving from boot camp to the Pacific WWII battlefield, and if Raoul Walsh’s war epic isn’t as disturbing or as honest as Full Metal Jacket, it does have indelible sequences and a cast that includes standouts Van Heflin, Aldo Ray, Mona Freeman and Nancy Olson (the latter two as the suffering women of soldiers).

Also made in 1955, Hell on Frisco Bay pits former cop and ex-con Alan Ladd against crime boss Edward G. Robinson in an inevitable showdown after Ladd tracks down who really committed the murder he was framed for. Always photogenic San Francisco locations are the real star of Frank Tuttle’s tidy but colorful film noir. Both films have superior hi-def transfers.

Carmen

La Bohème

(C Major)

New productions of the two most reliable warhorses in opera are distinguished by their leading ladies’ star-making performances. The title role in Carmen is played by the darkly smoldering French mezzo Gaelle Arquez, who burns up the outdoor Bregenz Festival stage whenever she’s front and center.

In La Bohème, Irina Lungu plays the pitifully sickly Mimi with immense strength and sympathy. Both productions also have top-notch hi-def video and audio; Carmen extras are director and set designer interviews.

Cymbeline

(Opus Arte)

This late Shakespeare romance is infrequently staged, so seeing Melly Still’s Royal Shakespeare Company production go off the rails is disheartening, since the cast is mostly effective, especially Bethan Cullinane’s powerful Innogen (Imogen for those who don’t think her name was misspelled in the first folio).

The music and dance interludes seem less organic than tacked on, which drags down the rest into an unfortunate mess of dramatic and poetic stumbling. The hi-def images are excellent.

Lulu

(BelAir Classiques)

The anti-heroine of Alban Berg’s unfinished opera has as its best and most prominent assayer German soprano Marlis Petersen, who gives Dmitri Tcherniakov’s tricked-out, fitfully pointed 2015 Munich staging its dramatic and musical allure.

Petersen does no wrong, whether splayed half-naked on the floor or being ruthlessly abused before running into Jack the Ripper. Kirill Petrenko conducts the Bavarian State Opera Orchestra in an incisive reading of Berg’s masterly score. The hi-def video and audio are first-rate.

Night School

(Warner Archive)

This turgid 1981 thriller—coming on the heels of Halloween, Friday the 13th and Phantasm, among others—spends its originality at the beginning, with the hideous murder of a victim on a playground mercilessly teased by her attacker before beheading her.

After that, the movie has two things going for it: a very pretty and poised Rachel Ward in her film debut, and the offhand unmasking of the killer. There’s a decent hi-def transfer.

The Nutcracker

Anastasia

(Opus Arte)

The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky’s beloved holiday ballet, gets a lovely Royal Opera production in honor of choreographer Peter Wright’s 90th birthday, brilliantly danced by talented soloists and corps de ballet, and sparklingly played by the orchestra under conductor Boris Gruzin.

The Royal Opera’s Anastasia, about the fabled Russian princess—and one of legendary choreographer Kenneth MacMillan’s most audacious works—scores superbly with the mesmerizing Russian ballerina Natalia Osipova in the lead, McMillan’s expressive movement, and the adroitly chosen music by Tchaikovsky and Martinů. Extras include interviews and featurettes.

Broadway Review—John Leguizamo’s “Latin History for Morons”

- Details

- Parent Category: Film and the Arts

- Category: Reviews

- Published on Tuesday, 28 November 2017 14:02

- Written by Kevin Filipski

Latin History for Morons

Written and performed by John Leguizamo; directed by Tony Taccone

Performances through February 25, 2018

|

John Leguizamo in Latin History for Morons (photo: Matthew Murphy) |

Despite TV and movie success, John Leguizamo cut his teeth with solo shows that began in small downtown theaters and gradually moved uptown after he became a known commodity.

His latest Broadway performance, Latin History for Morons, takes the form of a lecture to his audience about the mostly unknown (or forgotten) history of Latinos in America. It’s his usual combination of dead-on impressions, penetrating observations, juvenile humor and unabashed sentimentality.

When his 8th grade son came home from school one day and told him that he had a difficult history assignment—pick a Latin hero—Leguizamo realized that, in most textbooks, Latinos were basically written out of history.

So he made it his business to discover someone heroic for his son, and that became the springboard for the show, as Leguizamo speaks informally but intelligently how Latino culture has been systematically erased, from the Aztecs and Incas to the present day.

With a chalkboard at center stage to visualize the teaching concept (Tony Taccone’s direction is happily haphazard), Leguizamo blends his one-of-a-kind riffing, caricature and vocal impersonation into an offbeat lecture to discuss a scaled-down timeline of history, from the destruction of the Aztec and Inca civilizations by colonizing Spaniards to unknown Latinos (and Latinas) who fought in the American Revolution and Civil War.

All the while, though, he keeps returning to his family, and that’s what makes the new show particularly satisfying. His funniest lines come from his interactions with his wife, daughter and son—he gets hilarious mileage out of telling his kids that, back in the day, if someone wanted to steal music, one had to actually go to a store and shoplift—as well as the most heart-on-the-sleeve moments, especially the ending, when his son reveals the hero he finally teased out of his father’s sometimes inept but always well-meaning attempts to teach his son his own history, which is anything but moronic.

Latin History for Morons

Studio 54, 254 West 54th Street, New York, NY

LatinHistoryBroadway.com

More Articles...

Newsletter Sign Up